Learning While Teaching

Learning While Teaching

CREATING EQUAL SPACES FOR STUDENTS WHILE PURSUING A MASTER'S AT LOYOLA

Nestled between an array of trees, a grand sidewalk leads students and visitors toward six pillars that mark one entrance to a historic Chicago Public School. Here, Kevin Ho teaches students of Edgewater’s Nicholas Senn High School. Along with teaching, Ho is pursuing Loyola’s Master of Education degree through the Language, Culture, and Curriculum program.

Ho participates in asynchronous courses that the Language, Culture, and Curriculum program has carefully sculpted into a flexible course load that is able to meet the needs of many graduate students. “A lot of the learning activities are reliant on the information and work of other people in our cohort. For example, we have discussions with our colleagues on a variety of platforms–these projects are ongoing, so we revisit work from weeks prior and add on. A community is formed through voice threads and living documents that really make us collaborate and reflect on each other’s work.”

Ho fondly recognizes the opportunities he has to implement his learning in his classroom. He believes Loyola has prepared him for a life of teaching amongst diverse student bodies while also tackling academic inequities. The student body of Senn High School boasts a wealth of diversity that ranks among the state’s most heterogeneous institutions. Ho is quick to acknowledge how Loyola’s School of Education programs have equipped him to reach students who come from a wide variety of backgrounds.

“I’ve always had the mindset that people are always students, that we’re learning every day,” says Ho. “I feel empowered and ambitious when it comes to working with multilingual students, especially students in sheltered instruction programs who could be refugees or immigrants, or coming from a household which only speaks their native language at home. I feel very empowered in creating change and dismantling current systems of inequity within schools.”

Ho is proud to be an outlier for many students’ typical encounters with prejudice and unmet learning needs in their classrooms.

Students at Senn High School walk through the hallway.

“In my classroom, our language learners feel safe and comfortable, surrounded by people with similar experiences to themselves through speaking another language, being a refugee, or being an immigrant. Oftentimes, it may be the only classroom where children feel safe speaking up and volunteering because, in our class, they have support,” says Ho.

A great deal of this support comes from the education Ho has received through Loyola’s Language, Culture, and Curriculum program, which provides him with the tools and knowledge to support students that other teachers may not have. “In other classes, they [students] might have teachers who aren’t certified or used to training people who speak other languages. Say, in math, we might have a lesson where we’re making ‘ants on a log,’ an American snack with celery and raisins. A lesson like that is difficult to translate. It makes students feel insecure, and it can trickle into other classrooms.”

Creating experiences that are inclusive for all students is a key component of the School of Education’s educational mission, and it is one which can be made difficult by texts and curricula which aren’t relatable to everyone.

"I feel empowered and ambitious when it comes to working with multilingual students." Kevin Ho

Ho elaborates on the consequences of an education that does not take the time to treat inequity. “Systems of inequality will continue within schools and trickle down into the world as well. It leaves students with not a lot of options beyond high school. Getting into and navigating college will be difficult, applying to something like a trade school will be difficult. They end up taking any opportunities which come to them, for better or worse. They’re left to fend for themselves after high school,” Ho says.

Ho uses his classroom to combat the loneliness that can be felt by English learning students by empowering them through lesson plans which engage students in their coursework and with one another. “Everyone has a story. Everyone has a background,” Ho says. “It’s drawing from that existing knowledge that fulfills potential–knowledge I can use to push them in order to support them.”

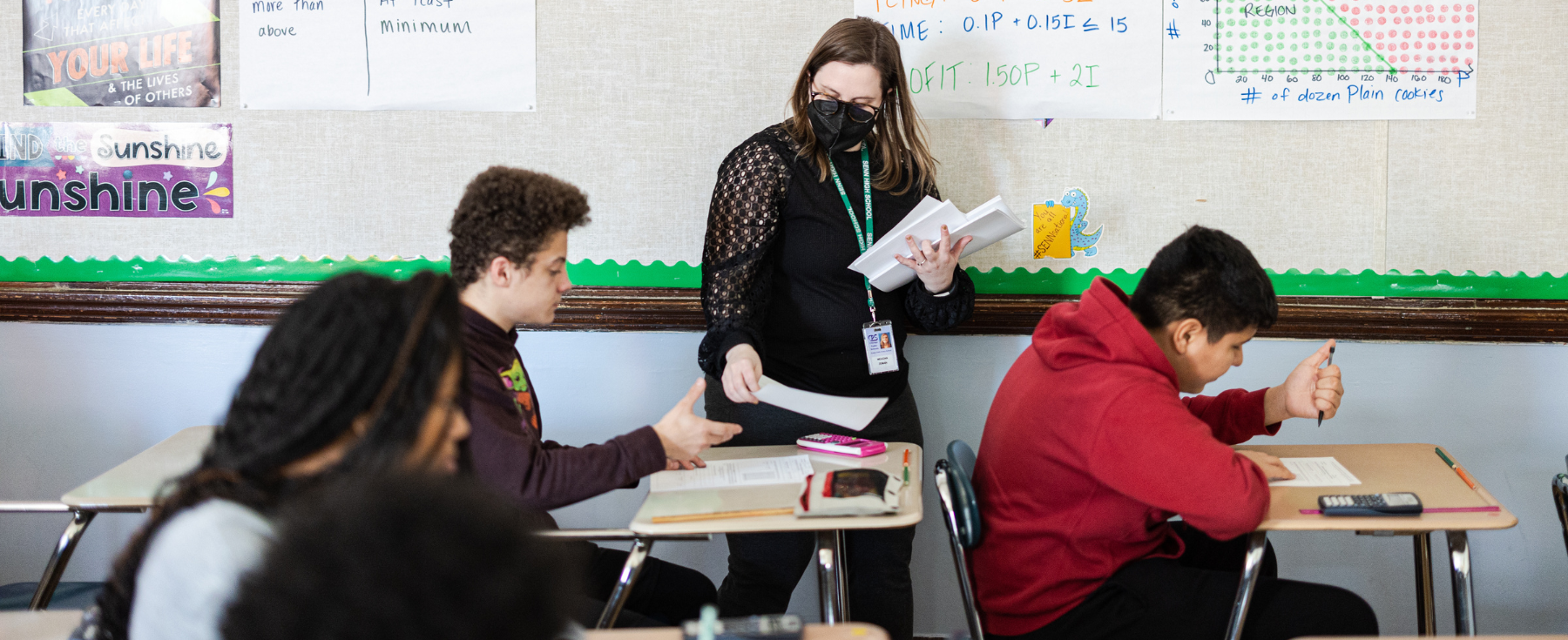

A teacher at Senn High School helps prepare students to succeed.

From his students, Ho learns a lot about what he values in his teaching practices and how he can best connect with the students he teaches. “I value joyful learning. We talk about issues in the world and locally. Sometimes these topics can be dark, and sometimes they can be heavy. I think it’s important to talk about subjects we need to shed light on,” says Ho. “Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, immigration, and so on. How do we have conversations with our students about this when they’re tough conversations to have? How do we bring hope back? How do we bring joy back?”

Drawing beauty from darkness is something that Ho feels necessitates a classroom where students are at the center–where their feelings are treated with care and compassion by both their teacher and their peers. “It’s about letting them know that they’re learning from someone who's not just me. They’re going to be in my world as well, they’re going to be teachers for their peers, and they’re going to be listening to their peers. You are going to be learning from other’s cultures, experiences, and languages,” Ho says. “I try to empower my students with the knowledge that what they know and their experiences are critical to this classroom. Students draw from their life and their identity with activities that push them into the center.”

“I value joyful learning. We talk about issues in the world and locally. Sometimes these topics can be dark, and sometimes they can be heavy. I think it’s important to talk about subjects we need to shed light on." Kevin Ho

Teaching students to recognize the value they bring to the table is a technique taught at Loyola’s School of Education. It is called an “asset-based” approach to learning. This is the opposite of a “deficit-based” approach, wherein teachers treat the students as problems to be fixed rather than opportunities to be activated. The School of Education emphasizes the importance of drawing out a student’s knowledge and allowing them to understand the boundless nature of their potential.

“I tell them, ‘What everyone here doesn’t know is that you all work a lot harder than a lot of my other students.’ Reaching your full potential isn’t about just being smart. It’s about working hard and having a strong work ethic. So never tell yourself that you’re not smart enough, because you are. And you always have been, and you’ve always been more than capable,” Ho says.

Loyola students discuss their teaching to benefit their abilities.

As a graduate student at Loyola, Ho is enthusiastic about the program’s focus on projects rather than coursework. “At the end, you create this final project which is built off of all of your prior work. Over the course of the semester, each week builds on top of one another as a component of this final project,” Ho says. “For example, we’re learning how to create professional development for teachers and staff. By the end of this, I’ll be able to host P&D programs for adults, and I actually am this Friday. I’m already applying class content, and I haven’t even finished it yet.”

Ho’s dedication to his students coupled with the opportunities he’s taken advantage of as a student of Loyola draws an impressive portrait of someone who has fully committed themselves to dismantling inequities and ensuring the confidence of vulnerable populations.

Although only in the germinal stages of a burgeoning career, Ho’s continual efforts toward creating safe and equal spaces for his students will provide countless possibilities for untold students.

Loyola is proud to host and forge minds like Ho’s that are setting the world on fire.

Language, Culture, and Curriculum

Classrooms and communities are more diverse than ever before, this program equips teachers with the pertinent understandings and pedagogical practices to holistically support and engage multilingual learners, also referred to as English learners or emergent bilinguals. Since multilingual learners of all ages develop and use language while engaged in learning, all educators can enhance their practice by adding lenses on language and culture to their curriculum. In addition to the Master’s degree, this program meets requirements for English as a Second Language (ESL) and Bilingual Education endorsements.

Nestled between an array of trees, a grand sidewalk leads students and visitors toward six pillars that mark one entrance to a historic Chicago Public School. Here, Kevin Ho teaches students of Edgewater’s Nicholas Senn High School. Along with teaching, Ho is pursuing Loyola’s Master of Education degree through the Language, Culture, and Curriculum program.

Ho participates in asynchronous courses that the Language, Culture, and Curriculum program has carefully sculpted into a flexible course load that is able to meet the needs of many graduate students. “A lot of the learning activities are reliant on the information and work of other people in our cohort. For example, we have discussions with our colleagues on a variety of platforms–these projects are ongoing, so we revisit work from weeks prior and add on. A community is formed through voice threads and living documents that really make us collaborate and reflect on each other’s work.”

Ho fondly recognizes the opportunities he has to implement his learning in his classroom. He believes Loyola has prepared him for a life of teaching amongst diverse student bodies while also tackling academic inequities. The student body of Senn High School boasts a wealth of diversity that ranks among the state’s most heterogeneous institutions. Ho is quick to acknowledge how Loyola’s School of Education programs have equipped him to reach students who come from a wide variety of backgrounds.

“I’ve always had the mindset that people are always students, that we’re learning every day,” says Ho. “I feel empowered and ambitious when it comes to working with multilingual students, especially students in sheltered instruction programs who could be refugees or immigrants, or coming from a household which only speaks their native language at home. I feel very empowered in creating change and dismantling current systems of inequity within schools.”

Ho is proud to be an outlier for many students’ typical encounters with prejudice and unmet learning needs in their classrooms.

“In my classroom, our language learners feel safe and comfortable, surrounded by people with similar experiences to themselves through speaking another language, being a refugee, or being an immigrant. Oftentimes, it may be the only classroom where children feel safe speaking up and volunteering because, in our class, they have support,” says Ho.

A great deal of this support comes from the education Ho has received through Loyola’s Language, Culture, and Curriculum program, which provides him with the tools and knowledge to support students that other teachers may not have. “In other classes, they [students] might have teachers who aren’t certified or used to training people who speak other languages. Say, in math, we might have a lesson where we’re making ‘ants on a log,’ an American snack with celery and raisins. A lesson like that is difficult to translate. It makes students feel insecure, and it can trickle into other classrooms.”

Creating experiences that are inclusive for all students is a key component of the School of Education’s educational mission, and it is one which can be made difficult by texts and curricula which aren’t relatable to everyone.

Ho elaborates on the consequences of an education that does not take the time to treat inequity. “Systems of inequality will continue within schools and trickle down into the world as well. It leaves students with not a lot of options beyond high school. Getting into and navigating college will be difficult, applying to something like a trade school will be difficult. They end up taking any opportunities which come to them, for better or worse. They’re left to fend for themselves after high school,” Ho says.

Ho uses his classroom to combat the loneliness that can be felt by English learning students by empowering them through lesson plans which engage students in their coursework and with one another. “Everyone has a story. Everyone has a background,” Ho says. “It’s drawing from that existing knowledge that fulfills potential–knowledge I can use to push them in order to support them.”

From his students, Ho learns a lot about what he values in his teaching practices and how he can best connect with the students he teaches. “I value joyful learning. We talk about issues in the world and locally. Sometimes these topics can be dark, and sometimes they can be heavy. I think it’s important to talk about subjects we need to shed light on,” says Ho. “Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, immigration, and so on. How do we have conversations with our students about this when they’re tough conversations to have? How do we bring hope back? How do we bring joy back?”

Drawing beauty from darkness is something that Ho feels necessitates a classroom where students are at the center–where their feelings are treated with care and compassion by both their teacher and their peers. “It’s about letting them know that they’re learning from someone who's not just me. They’re going to be in my world as well, they’re going to be teachers for their peers, and they’re going to be listening to their peers. You are going to be learning from other’s cultures, experiences, and languages,” Ho says. “I try to empower my students with the knowledge that what they know and their experiences are critical to this classroom. Students draw from their life and their identity with activities that push them into the center.”

Teaching students to recognize the value they bring to the table is a technique taught at Loyola’s School of Education. It is called an “asset-based” approach to learning. This is the opposite of a “deficit-based” approach, wherein teachers treat the students as problems to be fixed rather than opportunities to be activated. The School of Education emphasizes the importance of drawing out a student’s knowledge and allowing them to understand the boundless nature of their potential.

“I tell them, ‘What everyone here doesn’t know is that you all work a lot harder than a lot of my other students.’ Reaching your full potential isn’t about just being smart. It’s about working hard and having a strong work ethic. So never tell yourself that you’re not smart enough, because you are. And you always have been, and you’ve always been more than capable,” Ho says.

As a graduate student at Loyola, Ho is enthusiastic about the program’s focus on projects rather than coursework. “At the end, you create this final project which is built off of all of your prior work. Over the course of the semester, each week builds on top of one another as a component of this final project,” Ho says. “For example, we’re learning how to create professional development for teachers and staff. By the end of this, I’ll be able to host P&D programs for adults, and I actually am this Friday. I’m already applying class content, and I haven’t even finished it yet.”

Ho’s dedication to his students coupled with the opportunities he’s taken advantage of as a student of Loyola draws an impressive portrait of someone who has fully committed themselves to dismantling inequities and ensuring the confidence of vulnerable populations.

Although only in the germinal stages of a burgeoning career, Ho’s continual efforts toward creating safe and equal spaces for his students will provide countless possibilities for untold students.

Loyola is proud to host and forge minds like Ho’s that are setting the world on fire.