Why Major in History?

What can you do with a History degree?

Maybe you’ve loved History all your life. You were the kid who checked History books out of the school library even when you didn’t have a report due – biographies of Teddy Roosevelt or Martin Luther King; or big tomes with beautiful illustrations on life in Ancient Egypt or a Medieval castle. When you had exhausted the school library, you moved on to the public library. Then you discovered interlibrary loan and, of course, the infinite horizons of the internet.

Or maybe you never knew you liked History until you got to Loyola. Perhaps your grammar and high school didn’t emphasize it, or taught it to you as an exercise in rote memorization of a bewildering array of names and dates and wars and treaties. Perhaps you have been encouraged, even pressured by peers or those closest to you, to major in something more “practical.” Maybe you were good at your practical major; maybe not. And then it happened: perhaps in a Core History class -- it could be Western Civ. or American History, Latin American or Middle Eastern – or in an elective you took for the heck of it. You discovered that History was fascinating, that you loved it, that you were good at it and that you wanted to do more of it.

So now, you’re thinking about taking the plunge and declaring a History major. You’re looking forward to all those fascinating courses – about Tutankhamen or Chicago; pirates or the Ottoman Empire. There’s just one problem: how do you explain your choice of major back home? How do you respond when relatives or friends ask the inevitable uncomfortable question: “History!? – What are you going to do with THAT!”

This website is here to help you to answer that question.

In fact, it may help you to figure out what to do with the rest of your life. Why? Because this website is written by people, starting with yours truly, who came to the same discovery as you did, and faced the same questions about their post-graduate future. Like it or not, History is not usually perceived as a “practical” or lucrative major, mostly because it doesn’t train you for one particular job, the way courses in accounting or dental hygiene do. And there are plenty of doomsayers to tell you that you won’t get a job. We were told the same thing. That’s scary -- if not to you then, believe me, to your parents and others who care about you.

But this website is here to tell you and them that you’re going to be OK. In fact, what may seem a great disadvantage to History is actually an advantage. Study after study and lots of individual experience (from Loyola alumni and others) tell us that people often land jobs in fields other than the one in which they majored; that even when they do find a job in that field, they have to re-train and, often, within a few years, they find themselves doing something else. That’s just the way a modern economy works. Those who do best are not people who have narrowed in on a particular set of knowledge or skills; but whose range of knowledge and skills is both broad and fundamental: that is, people who know how to think (critically and creatively), people who know how to speak, how to write, how to debate, how to do research and how to make decisions on the basis of a dispassionate evaluation of the facts before them. For example, according to a study conducted by Debra Humphreys and Patrick Kelly of the Association of American Colleges and Universities and the National Association for Higher Education Management Systems 93% of employers report that

“a demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than [a candidate’s] undergraduate major.”

(cited here.)

In fact, it is our experience and that of our graduates that History imparts these capacities to students par excellence. In short, History’s great advantage is that it prepares you to do a wide variety of things well. What could be more practical than that?

This helps to explain why History and Humanities majors often do quite well in business and government. A recent edition of Business Insider (see here) identifies a large number of CEOs whose majors were in the Humanities, including:

- Ken Chenault, of American Express (History)

- Michael Eisner of Disney (English and Theater)

- Carly Fiorina, Ex-HP CEO (Medieval History and Philosophy)

- Robert Gates, ex-Secretary of Defense (History)

- Carl Icahn (Philosophy)

- A.G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble (French and History)

- Brian Moynihan, Bank of America's CEO (History)

- Mitt Romney, former Massachusetts Governor and Republican presidential nominee (English)

- George Soros (Philosophy)

- Peter Thiel of Paypal (Philosophy)

- Ted Turner of CNN (History)former IBM CEO Sam Palmisano (History)

Other prominent History majors include Joshua Marshall, founder and owner, Talking Points Memo and TPMMuckracker, Steve Sanger, CEO, General Mills, John J. Mack, Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley, and our own Jennifer Pritzker, financier and philanthropist. (For distinguished Loyola History majors, see below; for more information see here, which cites the studies noted above.)

Moreover, according to the study quoted above, while Humanities graduates earn less than those with degrees in pre-professional fields immediately upon graduation, they earn several thousand dollars more, on average, by the time both groups hit their peak earning years in their 50s and 60s. In short, persistence pays off for Humanities graduates.

How does History impart marketable skills and train you for a professional career?

History teaches its students to evaluate issues and societies in chronological perspective on the basis of the evidence left behind by human beings. History majors learn to evaluate that evidence critically, argue from it logically and speak and write about it clearly. This provides a deeper understanding of our own and other cultures, which, in turn, helps us to avoid oversimplification and stereotypes. Thus, History enriches us as human beings and makes us better citizens of the world. But it also provides skills and tools that make us eminently employable in a wide variety of fields. As a result, the History major is well-trained for life, for citizenship and for any career involving the analysis of data and its clear and persuasive presentation.

More specifically, in each of our courses, we try to give our students practical skills by teaching them how to read a document, perform complicated research, weigh evidence, assess, contribute to and decide complex debates. These are skills that anyone in a professional capacity needs. In short, History at Loyola will teach you:

a) speak persuasively

b) write effectively

c) think clearly and critically

d) construct compelling arguments

--grounded in solid evidence

--advanced with sound logic

--and which aspire to be true

OK, that sounds good, but do we really do this?

Well, every decade or so the History Department polls its alumni dating back to the 1940s. The most recent survey of all our graduates, in 2009, found that among 435 respondents, nearly 72% rated their history education as modestly relevant (23.6%), relevant (24.1%) or very relevant (24.1%) to their current occupation. Moreover:

a. 64% attributed much of their current speaking ability to their History education at Loyola;

b. 83% attributed much of their current writing ability to that education;

c. 87% attributed much of their ability to think critically to their education at Loyola University.

d. 79.9% attributed much of their ability to do research to their History education.

Our graduates tell us that armed with these skills, they have been eminently employable in a wide variety of fields, including:

- teaching at all levels, from kindergarten to University (25.1%)

- law (18.2%)

- government work (7.6%) (foreign service, the military, etc.)

- politics and community activism

- journalism

- computers, information archiving and analysis (3.5%)

- museum and archival work (3.5%)

- business and finance (7.1%); management (4.1%) sales (4.1%)

- healthcare (5.7%)

(For more careers and how to pursue them, see this chart: Careers for Graduates in History )

Though education and law are our most common destinations for our majors, the list of job titles among our responding alumni ranges from President, Vice President, Director and Senior Associate to Editor, Curator, Correspondent to Graduate Student and Artist to Bicycle Salesman and Barista. A number of our graduates have even become MDs, psychologists and engineers. People who do this report that their Humanities background often helps them in making judgments, relating to patients, and being aware of how public policy affects their profession (see wisdom from Loyola History alumni, below). Often, History can be combined quite successfully with STEM majors and History majors can increase their “marketability” on the job market by taking an accounting or marketing course.

Who are some of Loyola’s most distinguished History alumni?

- Amanda Adams, Attorney

- Megan Baumann, Social Media Consultant at Chicago Wilderness

- Mattias Baumberger, President, Schweizer Stiftung Farbe; Managing Director at Verband der Schweizerischen Lack-und Farbenindustrie (Swiss Coatings Federation)

- Greg A. Benbrook, Executive Director of Investigations, CME Group Market Regulation

- Prof. Alexander Bielakowski, US Army War College, Leavenworth Kansas

- Jerry Black, Attorney, Former Assistant Attorney General, State of Illinois, now CEO of Client Focus Inc.

- Kevin Blindauer, Client Service Manager - Vice President at FM Global

- Mary Botros, Proprietor, MB Classics Event Design

- Prof. John Boyer, Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of History, and Dean of the College, University of Chicago

- Christopher Carmichael, Attorney (Partner, Holland and Knight)

- Patrick Coogan, Associate Manager, Stanford Alumni Association

- Richard A. Devine, former State’s Attorney, Cook County 1996-2008

- Sonja Dimitrijevic, Attorney (Judicial Clerk at Illinois Appellate Court, First District)

- Tom Dreilinger, State Project Director at eLearning for Educators-Alabama

- Prof. Carlos Eire, Yale, Winner of the National Book Award

- Ray W. Francis, President and CEO Ray W. Francis Leadership Coaching and Consulting.

- Clare M. Hajduk Manager, Great Lakes Human Resources Management Service

- Carolyn E. Hartle, Attorney

- Thomas Jaconetty, Attorney; First Assistant Commissioner, Cook County Board of Review

- John Kloosterman, International Employment Attorney

- Travis Kluska, Program Officer at Community Investment Corporation

- Matthew Koch, Maritime Attorney

- Henry Kranz, Marketing Director, Oak Park-River Forest Community Foundation

- Timothy Leahy, Director of Government Affairs, Illinois American Water

- Beth D'Agostino Letscher, Assistant Vice President and South Sector Specialist, Real Estate and Community Development, St. Louis Economic Development Partnership

- Frank McAdams, Journalist, Film Critic, Author

- Anne McCuddon, Director, Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum; Historian of the Seminole Tribe

- Anthony McMahon, Director Coverage Oversight-Attorney, CNA Insurance

- Colleen S. McMahon, Vice President of Member and Volunteer Services, Council of Residential Specialists

- Prof. Peter McMenamin, Associate Chair of Clinical Practice, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine

- Prof. Steven P. Millies, Chair, Department of History, Political Science and Philosophy, University of South Carolina, Aiken

- Meredith P. Murphy, Attorney

- Patrick T. Murphy, Judge, Cook County Circuit Court

- Patrick O’Connor, Alderman, 40th Ward, Chicago

- James Pranger, Attorney (Partner, Peter J. Latz & Associates LLC)

- Col. Jennifer Pritzker, US Army (ret.), Financier and Philanthropist

- Prof. David Ross, University of Tennessee; trial consultant

- Susan M. Ruddy, Corporate HR Manager, Klein Tools, Inc.

- Richard H. Sanders, Attorney (Health Law Practice Area Leader, Vedder Price, P.C.)

- Caryn Schnierle, Associate Vice Provost for Enrollment Management, Illinois Institute of Technology

- Barbara Schwabauer, Attorney (Civil Rights Division, US Department of Justice)

- Prof. Peter Steinfels, Co-Director, Fordham University Center on Religion and Culture

- George Van Susen, Mayor, Skokie Illinois

- Mijo Vodopic, Program Officer, MacArthur Foundation

- Sara Wigmore, Attorney

- Nora Zei, Senior Director, Rotary International

But haven’t things gotten tougher for History majors during the Recession?

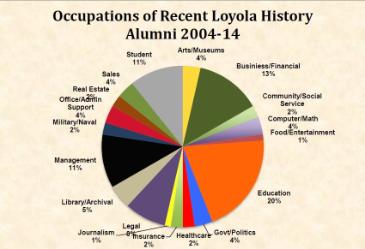

We were wondering about that ourselves, so in Spring 2014 we surveyed just the most recent graduates of the department, from 2004 to 2014. Of the 87 alumni who responded

- 70 said that they had found a job within the first year.

- 3 said that it had taken them 1-2 years.

- 6 said that it had taken 2-5 years.

- 5 were still in graduate school (but four of those were employed).

Once again, as for the whole population of Loyola History major alumni, our most recent graduates report a wide variety of career choices:

Sixty-one or 73% of those responding report that their Loyola History education prepared them or prepared them strongly for their current career:

What about our claim to provide skills? 50 or 58% of recent graduates who responded said that their Loyola History education contributed significantly or very significantly to their ability to speak effectively:

(Click for larger view)

83 or 99% of respondents said that their Loyola History education had contributed significantly or very significantly to their ability to write effectively

79 or 92% of the respondents to this question said that their Loyola History education had contributed significantly to their ability to weigh and use evidence.

(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)

(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)(Click for larger view)

Finally, we asked if their Loyola History Education had had a significant or very significant impact on their philosophy of life. For this group, 68 or 80% said that it had:

We believe that this survey of our most recent graduates reaffirms what has been true for over a century: the Loyola History degree prepares its graduates to compete successfully in the job market, pursue fulfilling professional careers and live rich lives. If you want to ask me more questions about this, I can be reached at rbuchol@luc.edu or 773-508-2594.

Please feel free to contact me and ask how we in the department of History are going to help you fulfill your life’s ambition.

Yours sincerely,

Robert Bucholz,

Professor and Chair of History

Still not convinced?

Don’t just take our word for the value of a Loyola History degree. Here is some wisdom from past Loyola History Graduates: Below, Loyola graduates from last year all the way back to a half-a-century ago offer career advice that shows, among other things, just how varied the opportunities are for the Loyola History major:

I had a great experience at Loyola. My time there had a significant impact on my life first in helping me get into an excellent graduate program and then, as my career developed, providing me with the intellectual and personal skills to be a useful and I hope, good, person.

My business career has encompassed international aerospace sales with Borg Warner; being the first female insurance representative in Illinois for Employers Insurance of Wausau handling corporate accounts; being the first woman to hold the position of Field Service Manager of operations at Mc Donald's Corporation in the early 1980's. I went on and earned a Master's in Education at the University of Memphis with the desire to apply education principles to business training programs. This varied career path was made possible by the very liberal arts curriculum I took at Loyola.

I became a healthcare practitioner as a physical therapist (BS and MS from Northwestern), and have had a full time practice providing orthopedic rehabilitation services for the past 30 years. However, during the past 9 years I have become increasingly involved in leadership positions within my profession at the state and national levels, and in advocating for the advancement of professional issues related to physical therapy, and more recently, to healthcare reform in general. The historical perspective I gained thru the History Honors Seminar program at Loyola inculcated in me an appreciation for historical, economic, and political dynamics that is sorely lacking in most of my colleagues who majored in the physical sciences and who thus generally lack any historical understanding. My perspective has been empowering to myself as well as thousands of colleagues across the country, since the impediments to professional advancement of the physical therapy profession have much more to do with historical, political-economic and cultural dynamics than scientific ones. This is why I consider my history education at Loyola highly relevant to my current endeavors.

Having a history background and degree not only helped me tremendously in my first career in the Army as a Military Intelligence officer, it also helped me develop a historical appreciation for objects I have encountered as a Master sport scuba diver. I have used various research skills to help me conduct research associated with underwater findings off the US east coast, in the Great Lakes, and in the Finger Lakes of NY state.

Yes!! First, I think the History program at Loyola is wonderful. It taught me to write and gave me a solid platform when it came to law school and my masters in the law. I think over all the professors were wonderful with of course a few exceptions here and there.

My education at Loyola University has been the background of my success as a professor, priest, and chaplain.

I really believe that my degree helped to prepare me for my career in association management as well as my graduate degree. The research skills that I learned have served me well with work projects and my master's thesis. All of the writing assignments helped my hone my skills and provided me with confidence in my abilities.

I have been an educator for 42 years...working at all levels from elementary to university level...I realized, long ago, what a solid foundation I received in the history department. Currently I am teaching U.S. history in Joliet and also methods of teaching history at Governors State. I also supervise field studies for future educators. I am very aware that much of my success in these areas came from a solid foundation at Loyola.

My history studies were excellent preparation for law school for two reasons. (1) The assignments included many papers and most tests were essays which required a great deal of writing. You must have excellent writing skills when you enter law school or you will struggle. (2) Many of the writing assignments involved analyzing historical documents and putting together (verbally or in writing) a theme based on those documents. In the practice of law (litigation which I do), you analyze appellate decisions and put together arguments based on your analysis of what those decisions say. The two activities are very similar.

The analytical, writing and research skills that you are learning will be invaluable in any job or discipline. Do not limit yourself.

I studied history because I loved it. Many people question how valuable a degree in history is but many don't realize the skills you gain in writing, speaking, researching and most importantly, critical analysis. Those skills can be applied to any career.

Do not limit your career choices. All of my degrees are in Liberal Arts and I was able to be successful working for the government and now in private industry.

If you are not sure if you want to teach, pursue advanced history studies, or law school etc... enhance your undergraduate degree with a minor in management, computer science, economics, or statistics to help gain employment after graduating. Take many business classes in addition to Liberal Arts classes in order to provide additional context for your historical studies and to provide a frame of reference for your interpretation of current world events that are extremely impacted by the biz world.

Even if you don't pursue history as a career, it will prepare you for a broad spectrum of opportunities. Also, it will give you perspective on current events and a greater world view.

Study hard. Attend classes. Have fun. Don't miss the opportunity to attend Rome or meet new people and make great friends.

Take business courses along with your major- Economics, Global and International Studies, Business Law, Finance and Accounting.

Learn the lessons of history, and have a successful and challenging career path. Explore as many career opportunities as you can - internships, long-term volunteer opportunities - in a broad variety of fields. The critical thinking you learn as a History major gives you skills that can be used across the economic spectrum.

There is a lot of writing, research and critical thinking as a history major compared to other fields - it is worth it. Those are skills that are valuable in many, many jobs.

If you love history, but don't wish to pursue teaching or a post in academia, don't be afraid to major in history…history teaches a multitude of things, and relationships with people can be enriched and become valuable cue to the knowledge of history which encompasses art, language, literature, politics, religion, diplomacy, business and economics (the list goes on). Knowledge of history in its totality is very valuable in any social or business setting, and a history major is one who understands the issues that we witness on the news every day.

The degree is versatile in that you can use it to enter any number of fields. It also provides a good analytical background for research, investigations, etc.

History is more of a backbone major. You do not graduate with a history degree and automatically fit into a particular job. But what it does teach you is the ability to communicate, research, intelligently discuss, and extends your writing abilities. Overall I think being a history major allows a person to be more well rounded than any other major because it makes you call on the past to understand the future. It allows for a student to venture into other avenues such Law, business, etc.

Find an internship which will give you some idea of what field you might go into after you graduate, and where in your history degree might take you. The more you can learn about possible career choices in History the better...

If possible spend a semester or two at the Rome Center

Know that you might not work in the historical field, but you will receive a great work ethic that will take you far in life.

I would tell a current undergrad History major that they are involved in a curriculum which can provide more benefit to their life than any other major. The skill set that they are provided with, namely analytical skill, effective researching, and the understanding of how social and cultural relationships develop and grow, will serve them well in virtually any occupation they pursue. Just a few of them are Law, Politics, Journalism, Public Policy, and Management as well as Education. The watering down of the Social Science curriculum as a whole in the last thirty five years at the elementary and secondary levels have resulted in almost three generations of citizens that know little of history other than what they get in the movies.

Learn how to write and do research well--they can open many doors.

This is the time in your life that you have to learn. People will tell you that a history degree is "useless" but it has been incredibly useful to me. I learned analytical, organizational, and writing skills that are invaluable in life after graduation. Also, because of the classes I took at Loyola I became a much more interesting person. On job interviews, I have talked about different aspects of my history degree that I enjoyed, and I was hired at my current job because in my interview I was able to talk about a wide variety of topics, including the history of early Christianity.

Take a course in introductory accounting and one in general business practices as electives, and a course or seminar covering how to job interview.

On the one hand try to figure out what you really want to do with the degree because other than teaching, I've never really been able to figure that out directly; and on the other hand know that I've bumped into history majors doing just about anything you can imagine, so don't let it limit you.

Don't worry about everyone asking "What are you going to do with a history degree?". The skills you develop, specifically research and writing, are desired and valued in many fields.

History is an excellent foundation for any profession; if only because it is not about "memorizing" dates, facts etc. The fact is we live our lives trying to understand our past, hoping to change our future. A historical perspective is always relative, and I truly believe that if we all understood that one truth, the world would be a better place. I am not implying that truth is in any way relative, I don't believe that, and I have strong Catholic convictions. I do believe that historical "perspectives" are relative, and if we all understood that better, we would understand each other much better.

I would tell current history majors to worry less about where you will find employment at the end of your time at Loyola, and simply follow your academic interests to the fullest. Jobs will come; the history department at Loyola teaches you to be analytical and to be articulate in your reasoning. These are skills that will suit you in any profession, and will make you valuable to any employer. But while at Loyola, pursue your coursework for the good inherent in knowledge-in-itself - the academic pursuit of truth is a noble one in itself, and employment is something you can worry about when the time comes.

Best all-around education for the complicated world we live in.

History is an important area of study that will increase your understanding of the world in which we live.

My own education in history helped me understand diverse, complex fact situations and evaluate the relative significance of the elements of those situations. I would advise undergraduates not to underestimate the value and utility of a degree in history.

Take full advantage of the writing, researching and analytical skills you pick up as a History major. Content is important, but you are far more likely to use the skills mentioned above in the work place than your knowledge of historical events.

I was double history and political science major and now I am in graduate school studying public policy and administration. Additionally I have held government jobs since graduating from Loyola. Whether as a graduate student or professional my history education has helped me the most, without a doubt! I enjoyed the political science program, but my history major is invaluable to me.

The basic skills learned in your undergrad years will serve you well in all your future endeavors.

And a few more sobering comments that help to explain why we devised this website:

I could have benefitted from having more guidance on how to make my History degree more transferrable to job skills when I started job hunting. A lot of people raise eyebrows at a History degree and question why you aren't pursuing teaching. History majors could benefit from developing an elevator speech and learning how to leverage their acquired skills for resumes.

I would recommend better career counseling for history majors, as this always bothered me, even as a student. Since I thought I would always be a teacher, I didn't worry too much then, but once I needed to make more money and left teaching, it has been forefront on my mind ever since.

Develop a serious well-thought-out plan for after graduation, and a serious well-thought-out backup plan, if you don't already have one. I guess that goes for all undergraduates, but maybe double for history/non-marketable majors. If you plan on law school, good for you, make sure you have a real plan, not just an idea. It isn't really a plan if you haven't run it by someone who can give well-informed feedback. If you don't already have a plan, get a minor in education so you can teach - even if you don't think / aren't sure you want to teach - it's better than waiting tables for God's sake! Don't think you can just walk in to one of those struggling school teacher programs like Teach for America - that was (one of) my big mistake(s). They may need teachers badly, but not social studies teachers. They need science and math teachers! All that's not to say studying history isn't worthwhile. The critical thinking and communication skills it helps you develop are very valuable in any job/field, but not immediately marketable anywhere.

Have a backup plan.

Careers in History

History teaches us to think historically, to see issues and societies in historical context. Just as we learn about individuals through their personal stories, so we become familiar with issues and societies through their histories. History leads us to a realistic appreciation of our own time by studying the past and enabling us to measure it against other times and societies. From history we develop a desire, and a method, to understand peoples and cultures, a mentality of great importance in our own pluralistic society and global world. History instructs us about the complexity of human affairs and helps us avoid oversimplification and stereotypes in our thinking. These are only a few of the educationally liberal attitudes and values that the study of history imparts. They enrich us as human beings and are valuable in any career or profession.

History and the Professions

The study of history develops precisely those skills of evaluation and analysis that will provide a firm foundation for any professional career. The work of the historian is to present analyses and conclusions based on evidence gathered and evaluated on the basis of established principles. No other undergraduate discipline will provide more practical experience in presenting and defending written and oral arguments. While other disciplines develop writing skills or understanding of political behavior, history combines the skills of these other disciplines with the added dimensions of the vast time span of human existence, and the breadth of view of a global perspective.

Superior Pre-Professional Preparation

In conjunction with the university's widely respected Core Curriculum, a major in history will provide the pre-professional student with a superior background for the pursuit of a career in any profession that requires skills in evaluation and analyzing evidence and data, as well as the ability to present one's analysis concisely and convincingly, both orally and in writing. These are the skills of the historian.

There are many options available to students who graduate with an undergraduate major in history. Whether in the public or private sector, historians can use their liberal arts training in a variety of situations and careers. Trained to be effective communicators, history graduates will have gained sharp critical thinking, analytical and writing skills.

Transferable Skills

Many of the skills historians develop while in school benefit them in the workplace. Research skills are just one example. Researchers need to formulate questions, create methods to find the correct answers and apply the findings to contemporary society. These skills are essential to the history profession, but also serve other careers in the public and private sectors. Historians with these qualities can find placement in the corporate setting, in a private history firm or as a journalist, for instance. Historians also are taught to be effective communicators, and good writing is essential in any profession. Below you will find more specific career paths for those with history degrees.

Business and the History Major

Of Loyola's history graduates, 39 percent have followed careers in business and management. A history major's training includes practice in the clear oral and written formulation of problems and solutions, analyses of causes and effects, experience with concise written arguments supported by empirical evidence and a sensitivity to different social and cultural points of view: all important skills and attitudes for a business career. The Loyola history major has a specific opportunity to study the modern urban cultures in which many contemporary businesses operate.

Students interested in both history and business, or in pursuing a business career while majoring in history, might consider a minor in the Quinlan School of Business. The following courses, recommended by the School of Business, would give history majors an attractive grounding for business employment:

- Accounting 201: Introductory Accounting I

- Economics 201: Principles of Economics I, and/or

- Economics 202: Principles of Economics II

- Information Systems 247: Computer Concepts and Applications

- Finance 332: Business Finance

- Legal Environment of Business 315: Law and the Regulatory Environment of Business

- Management 301: Managing People and Organizations

- Marketing 301: Fundamentals of Marketing

History Major for Pre-Law Student

A major in history provides you with an outstanding background for a career in law. Listen to the words of several lawyers (and former history majors) practicing today:

"The study of history enhanced my skills as a lawyer by requiring close reading and careful writing, and teaching me that, in arguing a point, eloquent phrasing is no excuse for inadequate support."

—J. T., Chicago lawyer, bankruptcy and insolvency law

"Much of the law is based on precedent, reviewing and analyzing what previous courts have done under similar circumstances. A lawyer has to understand the decisions of those prior cases, appreciate the context and trace the development of the law through to its current holdings. This is the historical method, par excellence, for which the undergraduate study of history provides, if not the only, then the best preparation."

—T.D.R., Chicago lawyer, intellectual property law

"My undergraduate study of history served me well in law school--and beyond. It required me to consider a particular set of facts (or, in many circumstances, competing versions of "facts"), draw conclusions as to their causes and effects, explain away or, at least, criticize alternative theories, and articulate my thoughts in writing."

—E.D.J., Chicago lawyer, professional liability insurance

Loyola's Department of History provides an excellent background for both law school and the legal profession. History 372 and History 373 are devoted to American constitutional and legal history. Moreover, apart from specific courses, historical research in every history course is very close to legal research; in history you use "primary sources" from the time period you are studying; in law, you work with the "case law" of the past to argue your present points. Close reading of texts and the analytic skills needed to make sense of them are the same for both. This is probably why history majors have among the highest admission rate to law school.

The American Bar Association advises against specifically "pre-law" courses. Instead, history majors prepare for legal careers by developing their research, writing and analytical skills. The small size of the department's 300-level courses allows close interaction between students and faculty, which is very useful when you need letters of recommendation.

History majors interested in law school are strongly urged to engage in law-related internships during their junior and senior years. Some such internships can gain academic credit through the Internship in History Program. Such work experience (1) helps you decide whether you really want a legal career, (2) makes it easier to find legal work after graduation and (3) helps you get into a good law school.

A number of organizations in the Chicago area have student internships in law and government. They include:

- Government agencies, such as the US State Department; the Mayor's Office's Department of Policy; Cook County State's Attorney; US Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Legal Assistance agencies: Legal Assistance Foundation of Chicago; Loyola University Community Law Center and Child and Family Law Clinic; Centro Romero (immigration assistance); Cabrini Green Legal Aid Center

In order to obtain the most desirable internships, you should plan ahead. History majors interested in a pre-law internship should meet with the department's internship coordinator as well as their departmental advisor for assistance in finding an internship and preparing a resume.

Important Pre-Law Links

- Loyola-recommended timetable for pre-law majors

- Recommendations for prelegal education from the American Bar Association

- Information about the LSAT exam, including online registration and sample exam: Law School Admission Council

- Legal Resources Guide links to many pre-law Websites, including several related to financial aid, law school rankings and LSAT commercial preparation programs.

Sample History program for those planning on a career in law:

Freshman Year

| Fall | European History Core (HIST 101, 102 or 106) |

| Spring | American History Core (HIST 103, 111, or 112) |

Sophomore Year

| Fall | Non-Western History Core (HIST 104 or 108) History ___ (300 level Pre-1700 European History) |

| Spring | History History ___ (300 level elective) |

Junior Year

| Fall | History ___(300 level course in U. S. History) History 291 (Junior Colloquium) |

| Spring | History ___ (300 level Post-1700 European History) LSAT Preparation: Send in your registration for the June LSAT by April; take a course in LSAT preparation (optional) |

| Summer | Take LSAT in June; Release college transcripts to LSDAS; Request applications from law schools. |

Senior Year

| Fall | History ___ (300 level course in Africa, Asia. Latin America or the Middle East) History ___ (300 level elective) Last chance to take LSAT or retake LSAT September—solicit three faculty members to write letters of recommendation on your behalf. October (if possible)—submit law school applications |

| Spring | February—File forms for financial assistance; Check law schools to be sure your application is complete. |

Secondary School Teaching and the History Major

Students interested in teaching history at the secondary or middle school levels can complete their State of Illinois Secondary Teaching Certificate at the same time as their history major. (Note that secondary certification in Illinois requires a major in an academic discipline such as history.) Students who do so will be qualified for a teaching job immediately after graduation.

It takes careful planning to complete certification and a major within four years. If you're interested, speak with your department advisor and contact Charles Tocci at the School of Education at 312.915.6865 or ctocci@luc.edu as soon as possible.

Advanced Degrees in History

History majors should also consider graduate study in history at Loyola. Loyola's graduate history program includes master's and doctoral level degrees in American and European history. Students may also want to consider a career in Public History, a discipline which entails the application of the skills and methods of history to the study, management, preservation and interpretation of historical records and artifacts. Public historians put their skills to work in a variety of professional situations: archives, museums and historical societies, historic preservation and cultural resource management program, local, state or government research, or neighborhood and community projects. Recipients of advanced degrees in history can teach at the secondary, high school or university level, and have the option to apply their master's or doctorate to any number of professional careers.

For more information on careers in general, and for help with resume preparation, visit Loyola's Career Center.

“Help! My kid wants to be a History Major!”

I get it. I may be the chair of the Department of History at Loyola University Chicago, but I’m also the parent of college age children. Like me, you love your children. Like me, you work hard all of your adult life, you scrimp, you save, you do everything you can to protect them and coach them and get them to a really good school like Loyola. Now they’re in, and the opportunities before them seem unlimited—but so do the choices and the pitfalls. You can’t rest easy just yet. You want to help them to launch themselves into the world in such a way that they will be happy and safe. But what a world it is. Setting politics, crime and global warming aside, whether you get your economic news from the television, the internet or the newspaper, you know one thing: It’s tough out there. Sure you want your college graduate to find him or herself, to become inspired and knowledgeable and wise. That’s why you sent them to a Jesuit university. But you also want them to find a job—respectable, well paying, secure.

That’s what we want too.

Still, you might prefer that your offspring pick a seemingly more lucrative major that will train them for a specific job, like pre-med, nursing, marketing or accounting. These are fine choices, in all of which Loyola is a recognized leader. But what do you do if your son or daughter shows little interest in those fields; or if, having tried them, his or her grades don’t measure up? What do you do if, one day, your child tells you that he or she wants to be a History major?

This website exists, in part, to tell you that it’s OK. They will do just fine.

First, don’t panic. Each of our parents got the same message, and they all got over it. Your child has chosen to study History with one of the best departments in the country, nationally ranked on several occasions within the last decade (For more on the History Department at Loyola, see http://www.luc.edu/history/welcome.shtml). More importantly, they have chosen a discipline and a department with a proven track record in training our majors for fulfilling and often lucrative employment, as I hope to demonstrate later in this message.

But how can that be? I mean, what can you do with a History major, besides teach History? It’s not like there’s a recognized job category like “historian” in the real world? (Well, actually, there is: nearly every major institution or corporation in our society has at least one and often many historians and/or archivists to record that institution’s past and progress, archive its records, etc, including Congress, all branches of the military, IBM, General Motors, Baxter Labs).

The mass media is doing its part to scare parents with stories like:

…and

- “A Decline That Makes Economic Sense”—but read all the responses

…or

But there are also stories like these:

- “The Humanities in Crisis? Not at Most Schools”

- The Humanities, Declining? Not According to the Numbers.

- “30 People With 'Soft' College Majors Who Became Extremely Successful”

- “11 Reasons To Ignore The Haters And Major In The Humanities”

- “Humanities Degree Provides Excellent Investment Returns”

- “We Need More Humanities Majors”

- "Want Innovative Thinking? Hire from the Humanities”

- "Study Correlates Liberal Arts Education with Lifelong Success"

In fact, Humanities enrollments, like the job market, go in cycles. Study after study and lots of individual real-world experience (including that of alumni of this university), all tell us that people often land jobs in fields other than the one in which they majored; that even when they do find a job in their major field, they have to re-train and, often, within a few years, find themselves doing something else (see: “Does Your Major Matter”: here). That’s just the way a modern economy works. Often, those who do best and have the most fulfilling lives, are not people who have narrowed in on a particular set of knowledge or skills; but whose range of knowledge and skills is both broad and fundamental: that is, people who know how to think (critically and creatively), people who know how to speak, how to write, how to debate, how to do research and how to make decisions on the basis of a dispassionate evaluation of the facts before them. Thus, according to the College of Liberal Arts of the University of Illinois,

“Recently, 113 corporations were asked what skills were needed by recent grads to forge a successful career in business. They stated that the most important skill to have was good verbal communication, followed by the ability to identify and formulate problems, being able to assume responsibility, to be able to reason, and to possess the ability to function independently. These skills are best gained from the broad knowledge of human interaction, of society, of culture, and of the arts.” (see here)

According to a study conducted by Debra Humphreys and Patrick Kelly of the Association of American Colleges and Universities and the National Association for Higher Education Management Systems 93% of employers report that “a demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than [a candidate’s] undergraduate major.”

It is our experience and that of our graduates that History imparts these capacities to students par excellence. In short, History’s great advantage is that it prepares you to do a wide variety of things well. What could be more practical than that?

This helps to explain why History and Humanities majors often do quite well in business and government. A recent edition of Business Insider (see here) identifies a significant number of CEOs whose majors were in the Humanities, including

- Ken Chenault, of American Express (History)

- Michael Eisner of Disney (English and Theater)

- Carly Fiorina, Ex-HP CEO (Medieval History and Philosophy)

- Robert Gates, ex-Secretary of Defense (History)

- Carl Icahn (Philosophy)

- A.G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble (French and History)

- Brian Moynihan, Bank of America's CEO (History)

- Mitt Romney former Massachusetts Governor and Republican presidential nominee (English)

- George Soros (Philosophy)

- Peter Thiel of Paypal (Philosophy)

- Ted Turner of CNN (History)

- Former IBM CEO Sam Palmisano (History)

Other prominent History majors in business include Joshua Marshall, founder and owner, Talking Points Memo and TPMMuckracker, Steve Sanger, CEO, General Mills, John J. Mack, Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley, and Loyola’s own Jennifer Pritzker, financier and philanthropist. (For distinguished Loyola History majors, see below; for more information see here, which cites the studies noted above)

It is true that, according to the study quoted above, Humanities graduates do earn less than those with degrees in pre-professional fields immediately upon graduation, but they earn several thousand dollars more, on average, by the time both groups hit their peak earning years in their 50s and 60s. In short, persistence pays off for Humanities graduates.

Careers in History

History teaches us to think historically, to see issues and societies in historical context. Just as we learn about individuals through their personal stories, so we become familiar with issues and societies through their histories. History leads us to a realistic appreciation of our own time by studying the past and enabling us to measure it against other times and societies. From history we develop a desire, and a method, to understand peoples and cultures, a mentality of great importance in our own pluralistic society and global world. History instructs us about the complexity of human affairs and helps us avoid oversimplification and stereotypes in our thinking. These are only a few of the educationally liberal attitudes and values that the study of history imparts. They enrich us as human beings and are valuable in any career or profession.

For more information on careers in general, and for help with resume preparation, visit Loyola's Career Center.

“Help! My kid wants to be a History Major!”

I get it. I may be the chair of the Department of History at Loyola University Chicago, but I’m also the parent of college age children. Like me, you love your children. Like me, you work hard all of your adult life, you scrimp, you save, you do everything you can to protect them and coach them and get them to a really good school like Loyola. Now they’re in, and the opportunities before them seem unlimited—but so do the choices and the pitfalls. You can’t rest easy just yet. You want to help them to launch themselves into the world in such a way that they will be happy and safe. But what a world it is. Setting politics, crime and global warming aside, whether you get your economic news from the television, the internet or the newspaper, you know one thing: It’s tough out there. Sure you want your college graduate to find him or herself, to become inspired and knowledgeable and wise. That’s why you sent them to a Jesuit university. But you also want them to find a job—respectable, well paying, secure.

That’s what we want too.

Still, you might prefer that your offspring pick a seemingly more lucrative major that will train them for a specific job, like pre-med, nursing, marketing or accounting. These are fine choices, in all of which Loyola is a recognized leader. But what do you do if your son or daughter shows little interest in those fields; or if, having tried them, his or her grades don’t measure up? What do you do if, one day, your child tells you that he or she wants to be a History major?

This website exists, in part, to tell you that it’s OK. They will do just fine.

First, don’t panic. Each of our parents got the same message, and they all got over it. Your child has chosen to study History with one of the best departments in the country, nationally ranked on several occasions within the last decade (For more on the History Department at Loyola, see http://www.luc.edu/history/welcome.shtml). More importantly, they have chosen a discipline and a department with a proven track record in training our majors for fulfilling and often lucrative employment, as I hope to demonstrate later in this message.

But how can that be? I mean, what can you do with a History major, besides teach History? It’s not like there’s a recognized job category like “historian” in the real world? (Well, actually, there is: nearly every major institution or corporation in our society has at least one and often many historians and/or archivists to record that institution’s past and progress, archive its records, etc, including Congress, all branches of the military, IBM, General Motors, Baxter Labs).

The mass media is doing its part to scare parents with stories like:

…and

- “A Decline That Makes Economic Sense”—but read all the responses

…or

But there are also stories like these:

- “The Humanities in Crisis? Not at Most Schools”

- The Humanities, Declining? Not According to the Numbers.

- “30 People With 'Soft' College Majors Who Became Extremely Successful”

- “11 Reasons To Ignore The Haters And Major In The Humanities”

- “Humanities Degree Provides Excellent Investment Returns”

- “We Need More Humanities Majors”

- "Want Innovative Thinking? Hire from the Humanities”

- "Study Correlates Liberal Arts Education with Lifelong Success"

In fact, Humanities enrollments, like the job market, go in cycles. Study after study and lots of individual real-world experience (including that of alumni of this university), all tell us that people often land jobs in fields other than the one in which they majored; that even when they do find a job in their major field, they have to re-train and, often, within a few years, find themselves doing something else (see: “Does Your Major Matter”: here). That’s just the way a modern economy works. Often, those who do best and have the most fulfilling lives, are not people who have narrowed in on a particular set of knowledge or skills; but whose range of knowledge and skills is both broad and fundamental: that is, people who know how to think (critically and creatively), people who know how to speak, how to write, how to debate, how to do research and how to make decisions on the basis of a dispassionate evaluation of the facts before them. Thus, according to the College of Liberal Arts of the University of Illinois,

“Recently, 113 corporations were asked what skills were needed by recent grads to forge a successful career in business. They stated that the most important skill to have was good verbal communication, followed by the ability to identify and formulate problems, being able to assume responsibility, to be able to reason, and to possess the ability to function independently. These skills are best gained from the broad knowledge of human interaction, of society, of culture, and of the arts.” (see here)

According to a study conducted by Debra Humphreys and Patrick Kelly of the Association of American Colleges and Universities and the National Association for Higher Education Management Systems 93% of employers report that “a demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than [a candidate’s] undergraduate major.”

It is our experience and that of our graduates that History imparts these capacities to students par excellence. In short, History’s great advantage is that it prepares you to do a wide variety of things well. What could be more practical than that?

This helps to explain why History and Humanities majors often do quite well in business and government. A recent edition of Business Insider (see here) identifies a significant number of CEOs whose majors were in the Humanities, including

- Ken Chenault, of American Express (History)

- Michael Eisner of Disney (English and Theater)

- Carly Fiorina, Ex-HP CEO (Medieval History and Philosophy)

- Robert Gates, ex-Secretary of Defense (History)

- Carl Icahn (Philosophy)

- A.G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble (French and History)

- Brian Moynihan, Bank of America's CEO (History)

- Mitt Romney former Massachusetts Governor and Republican presidential nominee (English)

- George Soros (Philosophy)

- Peter Thiel of Paypal (Philosophy)

- Ted Turner of CNN (History)

- Former IBM CEO Sam Palmisano (History)

Other prominent History majors in business include Joshua Marshall, founder and owner, Talking Points Memo and TPMMuckracker, Steve Sanger, CEO, General Mills, John J. Mack, Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley, and Loyola’s own Jennifer Pritzker, financier and philanthropist. (For distinguished Loyola History majors, see below; for more information see here, which cites the studies noted above)

It is true that, according to the study quoted above, Humanities graduates do earn less than those with degrees in pre-professional fields immediately upon graduation, but they earn several thousand dollars more, on average, by the time both groups hit their peak earning years in their 50s and 60s. In short, persistence pays off for Humanities graduates.